Thick Through the Middle: How It Started

We are always more interesting than our stickiest problems

It was an early summer afternoon when I climbed through my bedroom window onto the roof above my mother's azaleas and prepared to jump.

This would be a bold move, not just because I was perched above our suburban front yard, mere feet from the street where anyone's parents might drive by, but because the jump was to be a group effort. Huddled with me on the asphalt shingles were freckled twins, Ann and Andy; our friend Amy, who owned a fringed surrey that we'd pedal around the street; and Lexi — two years older than me and the founder of the Dare Devil Club.

Lexi embodied the spirit of the Dare Devil Club. Even as a kid, she was lanky and model-perfect, high cheekbones and tawny skin framed by wild golden hair. She was funny, beautiful, kind and adventurous in a way the rest of us could never touch.

In short, she was someone who could make other kids want to leap 12 or 14 feet off a roof with her to earn our Dare Devil stripes.

*****

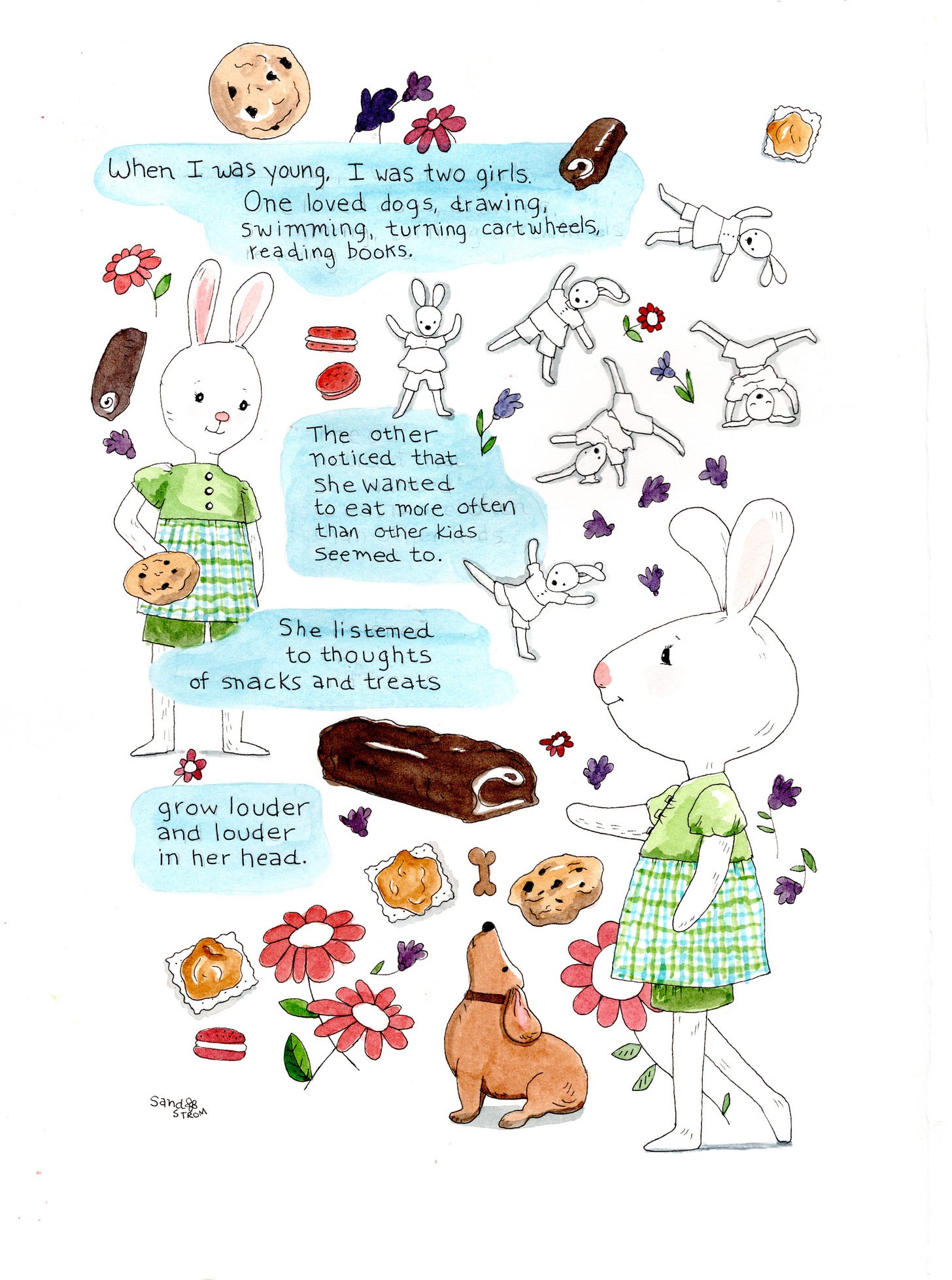

People with food issues tend to ruminate about how and when it all started. We might understand that the reasons are a complicated mix of neurochemicals, genetics, environment, psychology and social factors. Perhaps a trauma. Still, when did the first domino fall? Was there a crucial moment, before which we still had a shot at a life not colored by Twinkie-shaped obsessions and all that comes with them? It's demoralizing to think we might have been actually fated to roam the planet in a cloud of cravings, tight pants and shame.

This had to be someone's fault.

But I don't know. As far back as I can remember, I took pleasure in food at a level I now suspect was far beyond what most of my peers experienced. To this day, I can vividly conjure the scent of the shortbread cookies we got during snack time at nursery school. Nursery school. I was three.

I still taste the inch-high malt-colored frosting on my grandmother's brownies and feel the exquisite texture of my mother's chilled custard pie sprinkled with nutmeg. There were apple pies and angel food cakes and chocolate chip cookies. Meatloaf and cheeseburgers and pizza. Ho Hos and Ding Dongs and Oreos and ginger snaps. Vanilla bean ice cream under ravishing hot fudge. Strawberry milkshakes and chocolate milk and chocolate pudding and chocolate kisses. Aunt Helen’s homemade oatmeal bread. Shepherd’s pie. Crunch Bars and Reese's Cups and Tootsie Pops and peanut brittle stuck in my teeth. Peanut butter on an English muffin. Cinnamon toast. Cheese on Ritz crackers. Raisin Bran doused in sugar and milk. Grilled cheese and tomato soup.

None of us can know how another person experiences food, of course, but as far back as I can remember, most people I watched seemed to have a less grabby relationship with whatever they were eating. For me, the experience was always more than fueling up. Every meal and snack was a fizzy little sparkler lighting up part of the day.

It was something else, too. From a very young age, I used food as a Linus's blanket of comfort for my many fears. Those might not have extended to jumping off a roof, nor to exploring the woods or stealing colored wire from nearby houses under construction. Emotions, however, really undid me. I could be easily overwhelmed by sadness, loneliness, anxiety or rejection.

When I look back, it seems I had only one strategy when it came to self-soothing. Food did the trick. It always did. And it kind of worked for that, until my weight started to creep up and I started to compare myself to other girls my age; until the day in a department store dressing room, where nothing fit or looked right, and my mom lightly observed, "You're just a little thick through the middle."

Things got worse from there.

Anyone burdened by some chronic problem — addiction, disease, behavioral issues — can be tempted to frame and reframe their past around their affliction. But I think it's essential to remember that we've always been more than whatever our particular burden might be. Our issues don't make us special. Despite the amount of space they've taken up in our heads over the years, they're far from the most interesting thing about us.

Speaking for myself, I can say that I have a tendency to entertain a version of my life so far that casts me as the tragic heroine battling the scourge of food addiction, where the big question is will she win the war?

Yawn. I mean, sure. Yes. Whatever. The struggle is real.

But let us not forget that once I was a kid flying free atop the banana seat on my Sting-Ray. Once I was a girl who turned cartwheels and handsprings and drew pictures of ladies on poster board. Once I was very young and begged to be taught to read.

And once I was an official Dare Devil huddled on a roof and ready to jump.

*****

Andy went first. He scooched to the edge. Was this a good idea? The grass below didn't look all that far — surely it wasn't far enough to kill us, was it? — yet it seemed like something nameless, something I could not identify, might go wrong. On the other hand, we were Dare Devils. This was what was required, wasn't it? If something wasn't scary, it could hardly be a dare.

Without a word, Andy dropped off the edge, tumbling like a gymnast as he hit the grass. He was not dead. He was not even hurt. He was victorious. Certifiably, undeniably daring.

Ann waited only seconds before following her twin to her date with gravity. She hit the ground with perhaps less elegance than Andy, but with life and limb still intact.

Next up was Amy. She was the smallest, and even less daring, I thought, than the rest of us, who were faking our bravery. Amy was definitely scared. I could feel her fear as she moved toward the edge of the roof. She did not want to jump, but what choice did she have? Two devils had already dared and proven it possible.

She pushed off, hit the ground awkwardly and rolled a little before her hands flew to her ankle. Ann and Andy helped her up. Was she all right? Sure, sure. She was fine.

My turn. The key was not to think. The key was in trusting my friends and powering through the fear.

I scooched, dropped and hit the ground.

The lawn, it turns out, was deceptive. Beneath friendly blades of grass hid a surprisingly unyielding plot of earth — much harder than I'd expected. Bone-rattling, truth be told. Was I OK? I thought I was. Had I made it? I had. And like the others, I was still alive.

Soon Lexi brought up the rear and declared us Dare Devils. And we were. But we were not all unscathed.

Amy attempted to walk normally, but managed only a hobble. She tried her best to pretend she wasn't hurt, but it became clear that she needed our help to make it back home. Soon, unable to walk, Amy would confess to her parents that she'd been injured. Whether she coughed up the details, I never learned, but she was taken to the doctor and diagnosed with a sprained ankle. The surrey stayed in the garage for a long time after that.

As far as I know, my parents never learned of the jump, but I did tell my brother Eric. Amy's injury had frightened me, and I thought there was a good chance we'd all soon be in trouble. With 10 years on me, Eric had the words and wisdom to deliver a lecture more penetrating than anything my parents could have managed. How stupid we had been! We were lucky that one of us had merely sprained an ankle. I could have broken a leg. I could have hit the ground hard enough to blast my leg to pieces, bone poking right out through the skin. I was never to do that again. Never.

And I didn't, not only because Eric forbade it, but because the minute he described one of the possible consequences of such a thing, I did indeed see how stupid we'd been. Stupid and lucky.

For 50 years, the Dare Devil Club's big jump has stayed in my mind for a few reasons. First, Eric's warning marked my introduction to the concept of a compound fracture — a gruesome affliction that by turns repelled and intrigued me.

Second, it's harder to fathom how five reasonably intelligent kids could have concocted such a dimwitted plan. How did we get to a place where none of us saw the possible disaster?

Finally, there’s this. I have spent much of my life thinking of myself as a scaredy-cat who, given half a chance, will try to make it all better with food. A person who eats too much even though it comes with many terrible consequences. A high-functioning head case with mean carb cravings and many shameful pinchable inches.

All that is true.

But it's also true that I was a Dare Devil. I dropped off the edge of a roof and tumbled to the ground. Then I stood up again.

I'll admit it. I'm still sort of proud.

Surrey pedal car, Days of Yore.

I. Love this piece so much! This reminds me of what a complicated child I was. In another world I could have grown up to be a food-obsessed dictator. Kim Jong Un, but benevolent. Puberty eventually tames assertive, chubby little girls. But the appetite never really goes away.

And this is me: "A person who eats too much even though it comes with many terrible consequences. A high-functioning head case with mean carb cravings and many shameful pinchable inches.".... I read every word you write with excitement. Truly one of my favorites.