I Never Loved the Ballerinas

Spending quality time with a difficult man

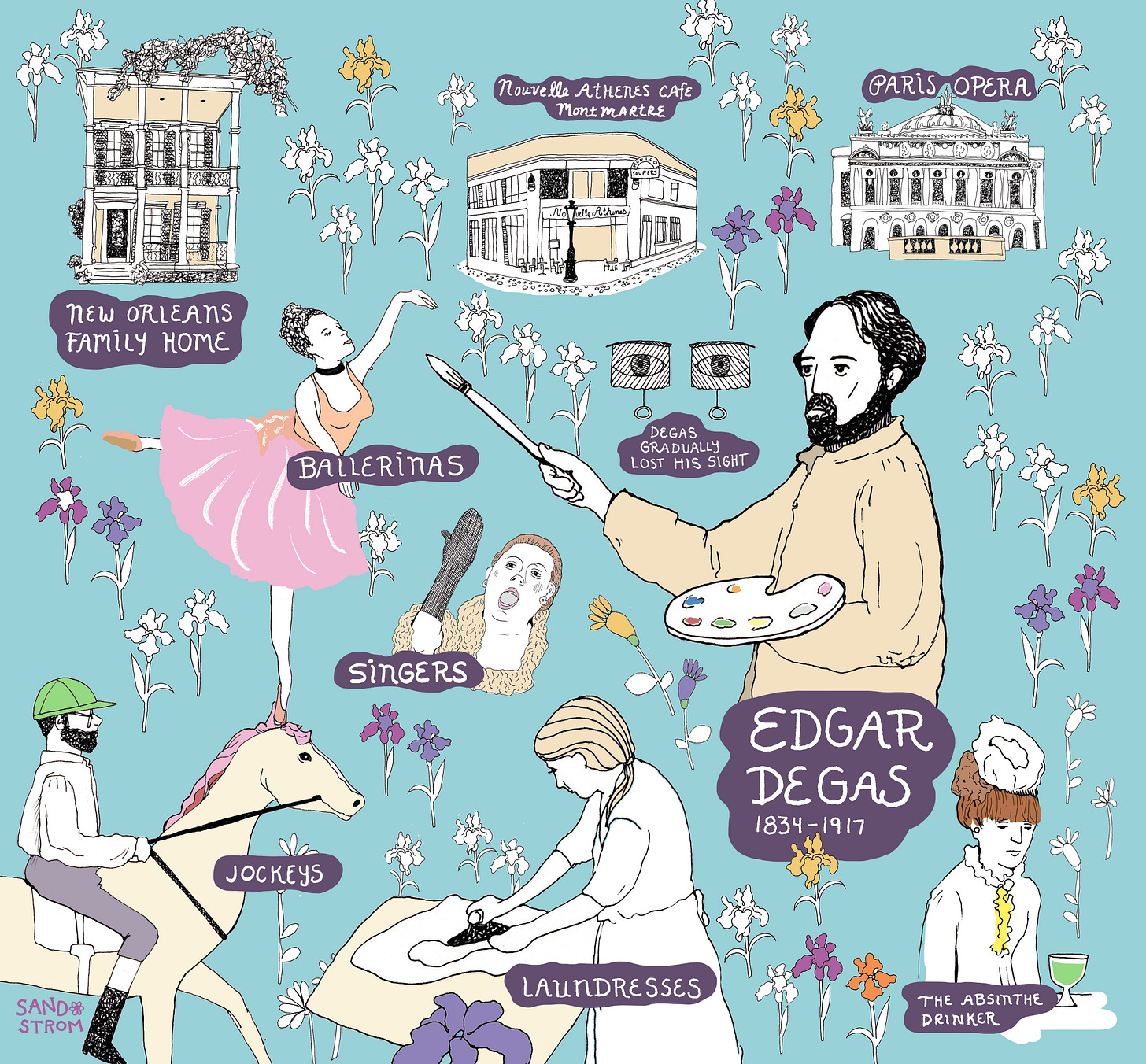

In the early 1870s, Edgar Degas made a series of paintings of musicians in the orchestra pit at the Paris Opera. To see them is to be confined in a tight space with a jumble of men standing shoulder to shoulder and frozen on whatever note each happens to be playing or not playing in that moment. The palette is heavy and dark: black jackets, black hair, deep brown benches. Flashes of peach indicate heads cocked this way and that. Behind and above the musicians, by contrast, we glimpse ballerinas in their pink and white tutus, incandescent in stage lighting.

These pictures capture time in a bottle. Well, lots of representational paintings do, I suppose, even the most formal portraits. But Degas was chasing the impossible: using a two-dimensional medium to depict movement. He succeeded in spades, I think. A viewer sinks right down into the pit with these guys, smells their sweat, hears the violins and the dusty thuds of pointe shoes on the boards. We are right there.

Two of these paintings are represented in a book simply called Degas, written by art historian Bernd Growe, and first published by Taschen in 1992. I bought it just after visiting the Cleveland Museum of Art's exhibition "Degas and the Laundress: Women, Work and Impressionism" and experiencing a kind of buzzy excitement I hadn't expected to feel.

Degas was never my favorite Impressionist. I had long put him in a column I labeled "ballerina art," and this was not a compliment. I had seen plenty of his ballerinas in museum fly-bys, and grudgingly accepted that his rendering was beautiful. But I felt put off by the too-pretty subjects and what I have learned about the brutality of their training. Any good feeling I have about ballet is limited to my pride that, five decades after taking classes at Gina Saunders' Dance Studio, I can still assume positions one through five in my kitchen while the vegetables cook.

But I never truly paid the ballerinas sufficient attention. That's the trouble with museum fly-bys. It's easy to treat the experience like checking off boxes in the seen-it column with no thought further than whether we liked it. Long before Instagram, there have been museum visitors who were scrolling and hearting, scrolling and hearting. It's nothing new.

Ballerinas aside, though, I have nothing against laundresses, so I was drawn to the Cleveland exhibition because of its tight focus on these 19th century working women. (Aside: Ballerinas are surely working women, too.)

Now, there was a lot going on in terms of why Degas and some of his peers focused on these women who washed, dried, ironed and hauled other people's clothes. These paintings invite us to consider the lives of the working class, but they also ask us to gaze at sensually rendered white skin and see that even as they pursued work that could be hot and leave them with aching muscles, they still inevitably experienced the sex-object once-over by employers and, yes, artists. This is addressed in the exhibition.

The paintings are beautiful. And, just like those ballerina canvases I dismissed; like the orchestra pit; just like his paintings of jockeys; like his cafe singers and circus performers; and just like that devastating painting "The Absinthe Drinker" — holy shot glass, Batman, have you ever seen such a lost gaze? — they are so skillfully composed that they put us square inside the frame.

Behold, the power of time travel. Not all art can do this; not all art aspires to do it. Degas broke from traditions of formal composition to give us the kind of things we can see in real life but that paintings typically had not shown.

It's easy for us to overlook that, because photographs and movies do this all the time now. But in his day, he was after not just presenting a view of a situation, but also conveying the feeling of it. Art builds empathy. And it's why I wanted more of Degas after seeing his laundresses.

This is where I must mention that to love the man's paintings is to struggle mightily with the man. On his good days, Degas seems to have been ... difficult. On the bad ones, he was a flaming anti-Semite and misogynist. The Dreyfus Affair, in which Alfred Dreyfus, a captain in the French army and a Jew, was unjustly convicted of giving military intelligence to Germany, divided France, including the art world. Degas turned viciously outspoken about his hatred of Jews. He severed ties with other artists, and reportedly dismissed models if he thought they were Jewish.

Degas died, it seems, a grumpy old man, physically blind and morally bereft.

You can find published arguments in favor of "canceling" Degas, which I guess in practice would mean that the laundresses never get their own show. I'll leave such conversations to others.

What I know is that I was deeply saddened to learn that the man was so deeply flawed, and I was also deeply moved by sinking into his work. Why is it that people who at their worst cause unforgiveable harm are so often the same people who at their best give us transformative works of art? I can't stop trying to figure out what I am supposed to do with this particular lesson that keeps asserting itself on humanity.

And still, there is no question that spending time in the company of a single artist or even a single artwork pays off in ways that the museum fly-by never can.

We humans are complicated. Artists may be more complicated than most. I'll never be able to un-know the insufferability of Edgar Degas, yet I will never unsee the laundresses, the dancers, the singers and the musicians. The absinthe drinker, God save her.

Degas sent them all to us across more than a century from something inside himself that reached toward beauty and truth. He caught the sublime. He gave it to you and me.

That is more than a small miracle.

Orchestra Musicians, 1870.

Detail from The Absinthe Drinker, 1875-76, painted at the La Nouvelle Athènes, a cafe famous for its artist clientele.

I love this essay. I’ve felt the same way many times--and, as you suggest, judging past artists ( or present ones) is a no-win stance. Who shall cast the first stone? Not me.

Thanks for starting my Saturday off on an intellectual note. I've shared this with my Facebook friends.